This article, by Museum Executive Director Janice O'Donnell, was also posted on Kidoinfo.

If you’ve visited the Museum in the past couple of

months, you may have noticed members of the staff with clipboards

lurking in the Museum’s newest exhibit,

ThinkSpace. Doing

some lurking of my own, I spent nearly 20 minutes watching a very small

visitor push big wooden beads along the wire and bead maze, watch them

slip down, push them up again. Twenty minutes – amazing concentration

for an 18-month-old. I tracked a 7-year-old who solved one

block-stacking challenge after another, translating abstract drawings

into three-dimensional models, and a 9-year-old who was determined to

map

all of the mystery mazes. I took notes, timed how long they

spent at activities, and listened for spatial language: “Rotate it!” “I

need another parallelogram.” A mom asked what I was doing.

“Observations,” I told her.

Careful observation is as important to the exhibit creation process

as planning, designing, building and installing. It’s how we know

what’s working well, what activities engage kids of what ages, how

adults respond, and what we should change. We expect to be surprised.

No matter how carefully we test prototypes and how much experience we

have, kids will do something we didn’t foresee. And sometimes we know

we don’t know, so we might put up a temporary label or try out a series

of easily changed activities and see what happens. We observe

systematically for several weeks after opening an exhibit and make

adjustments.

But our observation isn’t limited to new exhibits – it’s a constant.

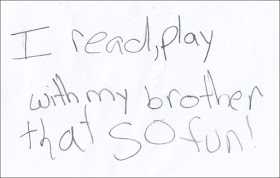

We record and share stories of the power of children’s play in the

Museum’s newsletter, on this blog, and on our documentation board in

Discovery Studio.

Watching kids at play helps us understand and appreciate their capacity

for and ways of learning, and we want our visiting adults to be as

delighted by their children’s ingenuity as we are. That toddler freely

exploring cause and effect at the bead maze encountered a perfect

learning opportunity, developmentally and physically within his reach.

One child, solving a mystery maze, said each of her steps aloud: “First

it goes down, then when I do this it goes that way, and then it goes

back and then down…” Another silently drew his solution. Different

styles, same determination.

Children can navigate social situations as deftly as they solve a

maze. I watched two previously unacquainted kids, ages 6 and 7, working

together to assemble seven large, unusually shaped blocks to build a

cube. A Museum play guide supplied well-timed hints, suggesting that

they “try rotating it” and offering other clues. The boys worked

diligently, incorporating the hints: “One two three four – that side’s

too high!” “Start again!” “Rotate!”

Five-year-old sisters of one of

the boys joined them and even when the younger ones sat on the blocks

and generally got in the way, the boys carried on. “Give me the

yellow,” one ordered his sister, who hopped off the yellow block and

handed it to them. After at least four start-overs, they could see the

solution. Some silent understanding developed among them that the

little girls would put in the last two pieces. The last block. The

boys could see exactly how it fit in, but the 5-year-old couldn’t quite

get it. “Rotate,” her brother told her. She turned it around and slid

the final piece into place. The boys climbed atop their completed cube,

arms raised in victory, while everyone cheered.

In a recent

blog post, museum planner Jeanne Vergeront suggests there ought to be an app for

play spotting,

which she describes as “… pausing and observing children at play. It

is watching them and getting to know them and their thinking through

their play. It is noticing what fascinates them and glimpsing the

intensity they invest in play.”

Children take their play seriously. We learn so much when we take their play seriously, too.